In this post, we’ll share an update on the evolving story of the place where Walnut Studiolo makes handcrafted goods, continue the documentation of our workshop evolution (photo essay), and share how living slow has changed us!

Jump to Section

This is the story of how we transformed our small urban lifestyle business into a slow-living homestead on 5 acres. It happened in phases:

Observing nature and making a plan while we acclimated to rural living

Planting trees and installing infrastructure

Developing routines for a resilient, slow-living homestead

Phase 1) Observing Nature and Making Plans While We Acclimated to Rural Living

In 2016, our family and business Walnut Studiolo moved from urban Portland to the rural North Oregon Coast. This move to the country was possible because we run Walnut Studiolo as a small lifestyle business. We brought our jobs with us, thanks to the internet and the postal service connecting us with folks around the world.

We moved in on New Years Day, 2016, after the holiday rush. Almost immediately after setting up the business in our huge new cavernous space, we worried, What have we done?

In this temperate rainforest, the raw steel tools developed a coating of rust nearly overnight. The paper used in shipping felt damp and limp. And we knew, if we didn’t take corrective action, the leather would start to mildew or mold soon. The new workshop was a simple pole barn, with no vapor barriers, heat, bathroom or internet.

There was a lot of problem-observing and problem-solving those first few years. In rural areas it’s just a fact of life that we have to be extra-organized, more communicative, and more self-reliant than we were in the city. We manage our own utilities (well, septic, and driving in recyclables to the transfer center). We need back-up systems for regular power outages, including water which is powered by electricity. With no delivery and few restaurants, we have to cook a whole lot more. Most modern conveniences and big stores are at least a 30-minute drive away, and sometimes 2 hours.

But bit by bit, we came up with solutions that made it work:

A French drain to redirect water from our doors

A commercial-size dehumidifier

An outdoor wifi transmitter and receiver to beam the internet a football field's distance away from the house

A large wood stove for heat and dehumidifying, as well as winter cheer

In addition to the lifestyle adjustments and running our business, we now had five acres to manage and steward: half forest and half sloped lawn. The forest half was more or less untouched for at least 70 years and largely self-managing. We were determined to protect the forest and leave it to be natural.

But the lawn requires constant maintenance to keep the workshop from becoming a bramble. We live in Tillamook dairy country where the grass grows thick and lush. We went through several mowers until we found one that could handle the grass, thorny weeds, and steep slopes.

While we got acquainted with the workshop and land, we kept careful observations and began making plans to improve both. We borrowed books on permaculture from the library and used those techniques to map out important features on our property, gained from over three years of observation:

How the sun moves along the horizon with the seasons, setting early behind the trees during the winter and late behind the mountains during the summer

Where the sunniest parts are: how hot the south-facing workshop wall gets with its metal siding, and how the north side never sees the light

How water moves on the land: slopes, drainages, and washouts

Where the infrastructure is located: highways, transmission easements, septic fields, well pumps, and utility lines

Phase 2) Planting Trees and Installing Infrastructure

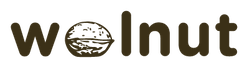

In 2018, we used the business’s savings to make the workshop more weatherproof for the products and tools, and more comfortable for us humans.

This workshop remodel project was a game-changer and set us up for the long haul:

Rodent-proof spray insulation on all surfaces, including closing up the ridge vent

Huge ceiling fans to keep air flowing and LED shop lights throughout

Replacing one of the huge bay doors with a covered front porch for mail pick-up

Interior drywalled entryway, bathroom, and kitchenette, with storage above

Plumbing that gravity-drains to the septic field

Weatherproofing and electric openers for the two large bay doors

Over several years, we also installed long-term infrastructure for the land. Our goals were to carve out gardens, grow our own food, reduce mowing, and suppress weeds on a 2.5 acre lawn:

- A laurel privacy hedge along the highway frontage. It made so much sense when we learned that the roots of the word “garden” are related to the word “guard.” To enjoy the land, to turn a lawn into a garden, it needed some protection and privacy. We snaked over 70 laurel bushes in an organic curved shape around the Walnut Studiolo monument sign to create an enclosed front yard. The bees love the laurel flowers and the birds love the laurel berries and nesting sites!

- Greenhouse. Before we could begin growing vegetables, we needed infrastructure. A greenhouse was like a “deer fence with benefits”: extending the growing season, controlling watering, and shelter from the wind. Although many greenhouse growers plant straight into the ground, we had such poor soil that we decided to install raised beds to be efficient with the amount of soil and compost we’d need to bring in. And to go easy on our backs!

- Deer fencing. The greenhouse was spaced about 40ft (12m) downslope from the south wall of the workshop building, so we added two short lengths of 7.5ft (2.25m) tall deer fence, enclosing the space between the greenhouse and the hot metal-clad south-facing workshop wall. This carved out a roughly 40’ x 50’ (12 x 15m) orchard that we planted with fruit trees, shrubs, and vines: kiwi berries, grapes, berries, apples, pears, cherries, currants, figs, native rose hips.

- Planting trees. We began by re-foresting the steep slopes in the transition zone between the mowed half and the forested half. The steep slopes were difficult to mow, and eventually the forest will shade out the blackberry bramble. Since we’ve moved in, we’ve planted over 40 trees, but there’s room for many more!

Phase 3) Becoming a Resilient, Slow-Living Homestead

Growing and cooking our own food has been life-changing.

As we began growing vegetables and fruit, we gained a greater appreciation of the natural systems and cycles of life they depend on. Care for the food evolved into care for nature, then care for ourselves, then care for community.

Composting

The garden begins and ends with composting. It closes the cycle of life, creating a place to input non-edible garden wastes, and an output of nutritious soil additives to increase yields.

First, we began composting to reduce landfill waste and save money on soil. But that quickly evolved into improving the land's fertility and creating more gardens. After trying several different kinds of composting bins, we settled into a system of lightweight, rollable compost bins that we place right on top of the weeds and let cold-ferment for at least a year.

After we’ve captured the resulting compost for the garden, the footprint underneath is bare and fertile, ready for planting flowers or deer-resistant edibles (like chamomile, rhubarb, or artichoke) to shade out the weeds underneath. Then we move the bin to a new location. And so we’re improving the soil quality and adding flower beds, one circle at a time.

Rainwater Harvesting

To reduce our reliance on aquifers and electricity, and use more of the rainwater that plants love for irrigation, we installed a rainwater tank.

Using the excellent book, Rainwater Harvesting, we calculated the size of the roof, the average rainfall for our area, and the amount of water it would take to irrigate the greenhouse during a long dry summer.

Then we were able to find a used 5,000 gallon rainwater tank to capture water from half the workshop roof, which is considerable in size. The roof is asphalt shingles and so the water is not potable, but now we have an emergency water supply, and the tank is upslope from the greenhouse so it's able to gravity irrigate our veg.

The Importance of Gardening

Growing our own food changed our lives because it made us slow down and appreciate what we have, in this moment. In this garden we’re building skills, maintaining our mental health, working our bodies, interacting with nature, repairing the land for the next generation, and increasing our self-reliance.

We were amateur gardeners at best when we got started. It took several years of getting to know our greenhouse before we were vegetable-gardening year-round with more confidence and better results. Our technique developed from a combination of the Square Foot Gardening , intensive French market gardening , and Eliott Coleman’s Year-Round Gardening . (Although we live in a mild climate that makes winter gardening fairly easy, Coleman proves that you can grow vegetables year-round just about anywhere, including his home state of Maine!)

The more we got into gardening, the more we came to appreciate it. We read books about gardening, watch TV shows about gardening, photograph our garden's progress, talk about our garden in the evenings, and we miss the garden when we're gone. The more we've explored, the more we've come to appreciate gardening as the solution to multiple problems.

Cooking What We Grow

Our kitchen garden gives us so much joy because we get to eat the results. This is a unique pride and satisfaction that is known among gardeners, but hard to explain to others. It's similar to the pride of workmanship and craftsmanship. We build our skills and experience gardening and cooking, transforming raw material into palatable food.

Beginning gardeners like us were advised to grow what we like to eat - but we can’t grow big luscious cantaloupes on the frigid North Oregon Coast! And trying to do so has been exercise in disappointment. We found it equally important to learn to love what grows, and how to cook it with the seasons. (A great way to do that before we began gardening was to subscribe to community-supported agriculture shares from a local farmer.)

Physical Exercise and Mental Health

Of course gardening is great exercise for the body. We don't need to go to the gym or use exercise machines anymore!

But the unexpected benefits of growing our own food have been mental and spiritual. Physical exercise alone is good for mental health, but there's something more, something special about gardening. Psychologists agree that “horticultural therapy” and garden activities have an “overall positive impact on several measures of mental well-being, quality of life, and health status.”

In other words, it’s good for the soul. When gardening, we’re in the present moment. Physically putting our hands in the soil can feel like grounding lightning. It taps into something deep and ancient within all of us.

Restoring the Environment

We’ve always grown our vegetables with no-chemical, organic methods, but that evolved into a goal of leaving the soil better than we found it, a practice known as regenerative gardening For example, in the middle of each raised bed we planted herbs and flowers for pollinators. It’s a win-win for us and nature: we get good yields of delicious food and insects enjoy the plant diversity. And while we’re gardening, we get to delight in cute fuzzy bumblebees rolling in the artichoke thistle and zippy hummingbirds hovering around the bean flowers.

We have noticed an increase in pollinators, birds, and wildlife on our land, in our garden. We get some comfort from knowing that we’re improving and repairing the land – that we’re doing our bit. Growing a climate resilience gardens is a powerful, hands-on way to do something meaningful for climate change. If everyone everywhere were gardening like this, the environment would be changed.

What’s Next?

With a large greenhouse, small orchard, and rainwater tank now under our belts, we’re starting to feel like a somewhat self-reliant homestead!

Our next steps?

Re-foresting. Plant more trees to expand and merge with the forest and reduce weed management.

More plants: medicinal, structural. We're learning more about plant medicine and herbal teas for our health, and coppicing trees for biodegradable garden structures and basketry.

Food forest. In 2025, we broke ground on a third food production garden, called a food forest . It’s a 50’ square (15m) block primarily for perennial edibles and medicinals. Our eventual goal is a mature and self-sustaining edible landscape of overstory and understory trees, shrubs, herbs, and ground covers working harmoniously together for passive food production.

New forms of food production. Ducks for eggs and slug control, and growing more pantry staples. Greater quantities of dry beans, growing our own grains and breadbaking, and planting nutritious oilseeds are all goals for next year.

Reflections on Slow Living

As we stop to take a pause for reflection, we recognize that we are not the same people who moved here nearly 10 years ago. This place has changed us, in a good way. A daily routine of productive and creative on-site work, food growing and cooking, and regular nature observations and gardening, has become a completely different lifestyle. This is slow living.

We’ve been on a journey since 2009, the year we founded Walnut Studiolo, and without our customers and supporters it wouldn’t have been possible. We didn't have examples to follow, but we hope our experience can be for others. We didn't come from entrepreneurial, gardening families.

In hindsight, we didn't have to move to the country to experience slow living. This was just the journey we went on to arrive here. We just had to start gardening, and shift our hobbies. An average yard in Portland is the same size as our greenhouse. Five acres is a lot to manage: it sometimes feels like too much for two people!

Gardening can be done anywhere: yards of any size, community garden plots, balconies, and even indoor gardening. Visiting and volunteering with arboretums, botanical and demonstration gardens. Frequenting u-pick farms or supporting gleaning projects. Eating seasonally can be accomplished with CSAs and farmers markets.

Slow living starts from nurturing and stewarding some earth and observing nature, grounding yourself in the settings. Experiencing awe and appreciating the present with gratitude. And that can be done anywhere.

With gratitude to you dear reader: we'd love to hear your thoughts and questions!

Ann Siqveland

September 14, 2025

Val & Geoff – Witnessing your love and dedication to the land over the last 10 years has been incredible, but reading this gorgeous and informative synopsis truly took my breath away. Love to you guys, can’t wait to come see these ever-evolving projects again! -Ann