How can we survive making crafts into the future? And is there any point to making crafts when machines and factories are so efficient, so prevalent, and make things so cheaply?

In this post, we're going to meditate a little on the value of craft and craftsmanship, and the future as we see it.

What is Craft?

There is no doubt that people are interested in crafters and craftsmanship. There are locally-made organizations like Portland Made or Texas by Texans. Obviously there is Etsy, the handmade marketplace, which is now a half-billion dollar company that is publicly-traded on the NASDAQ. If it cost the same, I believe people would choose to buy craftsman-made every time.

Unfortunately, it doesn't cost the same, and it's gotten hard to tell what craftsman-made even is anymore. Factory designers are brilliant at hiding the cheapness of their products. Their main goal is to make sure it lasts longer than the return policy.

Making things more confusing, words like "crafted" and "handmade" have even been "washed" by marketers, so now you can buy "handcrafted" McDonald's coffee. They seemed to have broadened the definition to include anything that was touched by human hands, ever (which is everything). Obscuring and diluting the meaning of what we do as craftspeople is as damaging as anything else in this line of work.

It's funny though, there's a range between handmade and handcrafted, from a glue-encrusted macaroni sculpture to an artistic masterpiece. Just as there's a fine line between a machine-made commodity and robotic-made precision parts. Factories can make barely-passable mass-produced crap, or they can produce elegantly-engineered products with robotic precision and speed.

Etsy has struggled with this definition spectacularly over the years. Good examples are when an artist draws a design and gets that printed on a t-shirt. They made the art, not the t-shirt, and in fact they used another company to silkscreen their art onto the t-shirt for them, but it is eligible for the handmade marketplace. Nobody makes every component of every thing. We don't make our own metal rivets or screws, yet they are necessary parts of what we make. So once you start drilling down on it, the line becomes very gray very quickly.

The harder you try to define what a craft or a craftsperson is, the more nuanced and wordy the definition becomes. There are certainly gray areas, but more often than not, like the US Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart said when trying to define pornography, I know it when I see it is still one of the few working rules. Which in the end is just subjective and arbitrary. For lack of any better definition, I guess I'd define craftsmanship as production without an assembly line, in a workshop and not a factory. Or, something made entirely by one person such that when a mistake is made or a change is needed, the maker can stop production, and fix it or change it rather than tossing it.

Craftsman vs Factory

So then the other night we watched the 2018 documentary "Takumi: a 60,000 Hour Story on the Survival of Craft" by Chef's Table director Clay Jeter and Lexus (like, the cars).

As a family currently surviving on old-fashioned craftsmanship, the title alone more than piqued our interest. We were enthralled with the idea of a 1200-year-old family business specializing in all-wood religious building construction, and the Japanese concept of a takumi - a master craftsperson who has practiced at least 60,000 hours.

As opposed to the American concept of 10,000 hours to mastery that Malcolm Gladwell popularized - the "magic number of greatness" - it only makes sense that in Japan it would take at leastsix times as long to become a master. During our visit to Japan, we visited several different traditional craft studios, and found that they felt uncomfortable calling themselves an expert at something unless they'd been doing that trade for generations, on businesses where they'd started as children, either inherited or interned. Meanwhile, amongst us Portland-style "makers" we thought of ourselves as accomplished at our craft because we'd been doing it at least five years (ha!).

In the documentary, the interviews with the Curator of Craft at the Smithsonian and the personal stories of the Japanese master craftspeople were intriguing and thought-provoking, but it wasn't too long before the documentary became basically a Lexus commercial, which seemed odd and out-of-place until we googled the backstory.

In the end, the documentary's own thesis was being compromised by its own producers. The reality was, in order to even afford a documentary honoring craftsmanship, they had to make it a car commercial, twisting and contorting a car factory job into a master craftsman role. It felt like desperation trying to draw a short line from the organic beauty of ancient Japanese craftsmanship to the angular beauty of modern Japanese production lines. I get what they were trying to say, but it wasn't a pretty fit and it felt a little dirty.

The Craftsperson's Edge

Meanwhile, another show we've been enjoying lately, this one on Netflix, is The Repair Shop. In this English show, people bring in treasured heirlooms and family possessions to a team of restoration experts for refurbishment.

Once again, there's a problem with the backstory when you follow the money - nobody on the BBC show actually pays for the repairs. With the amount of man-hours involved in painstakingly restoring a painting punched with pencil holes by children, or rewiring a vintage pinball machine, how many people could actually afford to pay for the repairs?

In our limited experience with repair work, we have often found ourselves in the same position as the people on the show. In our small community, it often makes more sense to trade our skills in repairing work for goodwill and trade rather than a living wage.

And yet, the very existence of the restoration experts, the teddy bear hospital ward and all, proves there will always be a need for hands-on skills. No machine could be programmed to repair a broken antique, at least not affordably.

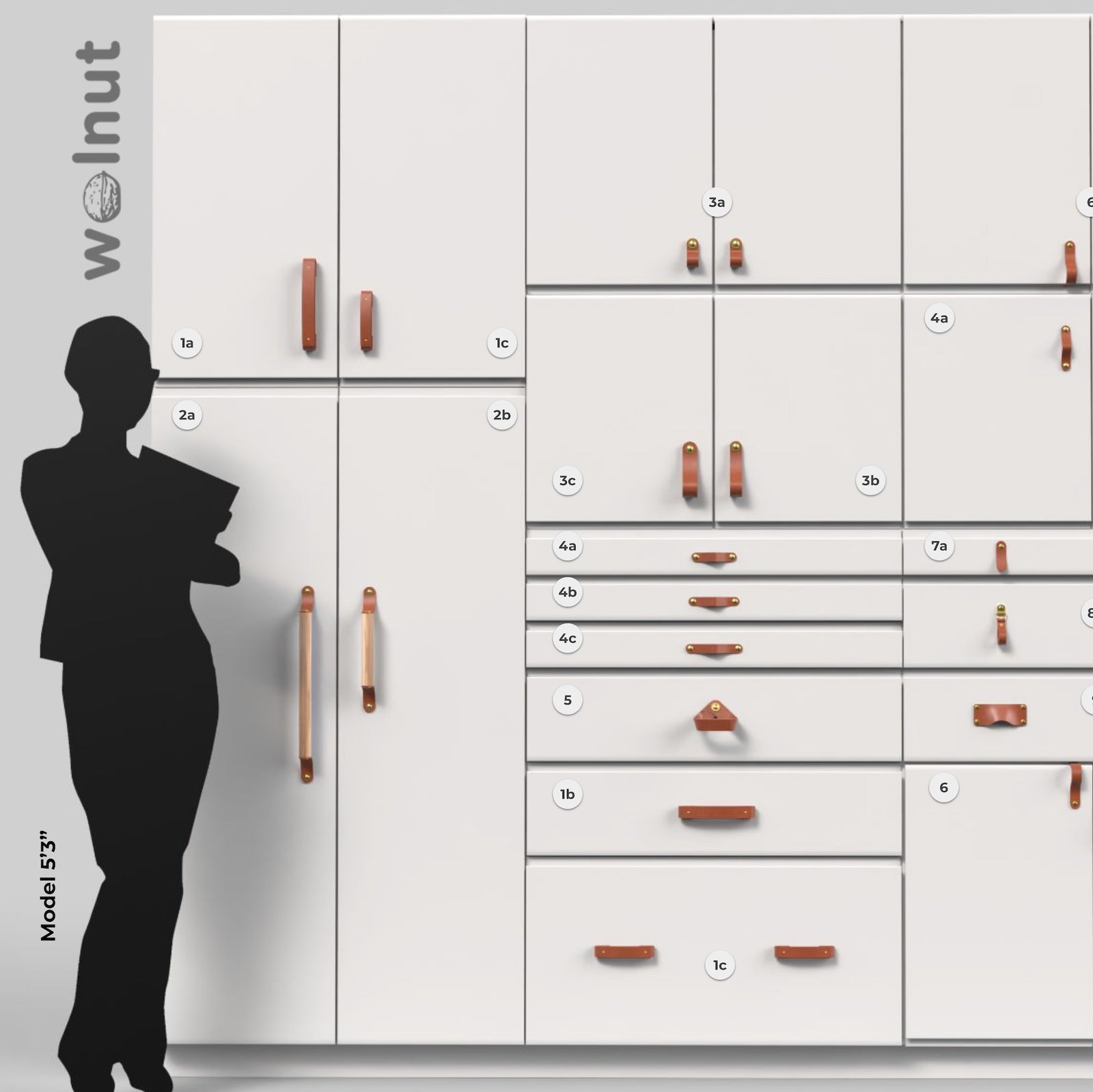

That's where craftsmanship will always have the edge: there will always be the need for that little thing. A machine is unbeatable when it is programmed to make hundreds or millions of something. But when you need one, or a dozen? When it's a unique, specialty product that only a handful of people need every year? When it just needs a tweak? In those cases, factories won't help. Factories get fired up to make things in the tens of thousands or more. They have to cast expensive molds, engineer special machines and even design robots so that every part can be fabricated cheaply.

And that's where we see the future of craftsmanship: in specialization, in customization, in personalization. It will be in matching the purposefulness and care of purchasers and makers. In catering to people, for whom the purchase itself is as personal as the time and attention we put into making it.

Leave a comment (all fields required)